We learn prime numbers in elementary school and then move on with our lives. Well, some people. One of the greatest living mathematicians, Terence Tao didn’t. But he’s not what this diatribe is about. I’m fascinated by the shear bredth of primes and how despite current mysteries in the field, what an increasingly meaningful role they’ll play in a world with more computers and more robots.

As of 2024, the largest known prime number is 2^82,589,933 – 1, a Mersenne prime. It would take a 3,500-page book to display its 24,862,048 digits in standard font size.

As a refresher, a number is considered prime if it meets these criteria:

- It has exactly two distinct divisors: 1 and itself.

- It is a positive integer greater than 1.

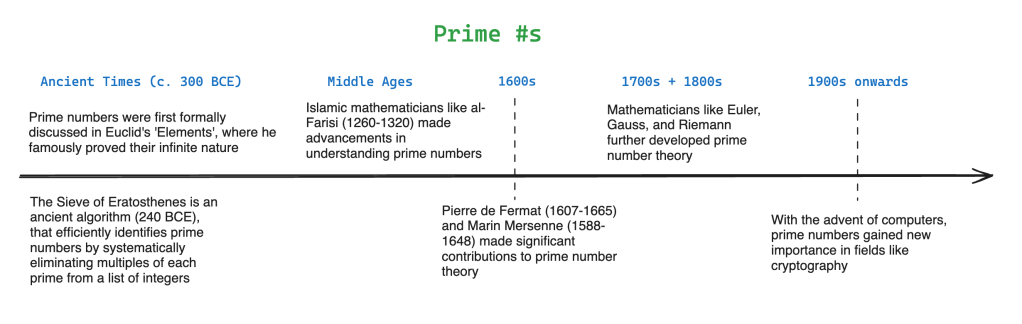

Euclid’s Theorem, proving the infinity of prime numbers, laid the foundation for millennia of prime number exploration and continues to inspire mathematical inquiry today.

But, there are so many types of prime numbers and they underpin a lot of key components of the lives in which we don’t pay attention to prime numbers.

Since when are numbers hard to find? It’s not like we’re toddlers playing a counting game asking our parents what comes next.

Yet, for very smart people who have access to insane computer power, finding certain prime numbers is still incredibly hard.

There are also many types of prime numbers. Any chatbot can educate you on the 10 common types of primes, but I won’t do that until the end of this post. But there are a couple with funny names I’ll point out that interesting patterns but have fewer direct applications compared to, say, Mersenne primes (Mp = 2^p – 1, where p is prime and Mp is also prime) – Sexy primes (primes that differ by 6 since sex means six in Latin) or cousin primes (primes that differ by 4), or Palindromic Primes (Prime numbers that read the same backwards and forwards).

cryptographic applications

Crypto is crypto because of public key cryptography. Which fundamentally works since it’s incredibly hard (aka plausibly impossible) to find the prime factors of really big numbers, but quite easy to verify that they multiply together to reach a certain number.

Consider this: removing milk from coffee without tools is nearly impossible, but verifying its presence is easy. This mirrors a key principle in cryptography:

Multiplication is simple: 17 × 23 = 391. Factoring is hard: finding 17 and 23 from just 391 is challenging.

Now imagine this with enormously larger numbers. The product (391) acts like a public lock, while the factors (17 and 23) are the keys. This concept underlies RSA encryption, which creates ‘locks’ that are easy to make but extremely difficult to break, thus securing our digital information. This is why primality (checking if a number is prime) and factorization are so important in cryptography.

Prime numbers, particularly specialized types like Mersenne and Wieferich primes, play a fundamental role in mathematics and its applications. These primes exhibit unique properties that aid in pattern recognition and problem-solving across various mathematical domains. In cryptography, understanding different prime types contributes to the development of robust encryption methods. The search for specific primes often advances computational techniques and hardware capabilities in computer science.

recent riemann breakthroughs

Despite significant technological advancements—including supercomputers, distributed networks, AI and quantum theories—many prime number-related questions remain unanswered. Notable examples include the unresolved Riemann Hypothesis (that has a $1M prize) and the elusive twin prime conjecture.

Both the Riemann Hypothesis and the Twin Prime Conjecture deal with prime number distribution. The Riemann Hypothesis suggests that all non-trivial zeros of the Riemann zeta function (ζ(s) = ∑ (1/nˢ) for n=1 to ∞) lie on a specific line in a complex plane, which would provide deep insights into prime spacing. The Twin Prime Conjecture posits that there are infinitely many pairs of primes differing by two. Proving the Riemann Hypothesis could offer tools or insights that help address the Twin Prime Conjecture and other prime-related problems.

Yet, there have been some recent developments. In May of this year, Maynard and Guth published research indicating that the zeros of the Riemann zeta function become less frequent further from the critical line. This implies that any violations of the Riemann Hypothesis would be rare. Their work provides more precise tools for estimating how often the zeta function’s zeros occur, refining our understanding of prime number distribution

Yet, there have been some recent developments. In May of this year, Maynard and Guth published research indicating that the zeros of the Riemann zeta function become less frequent further from the critical line. This implies that any violations of the Riemann Hypothesis would be rare. Their work provides more precise tools for estimating how often the zeta function’s zeros occur, refining our understanding of prime number distribution

While this doesn’t prove the Riemann Hypothesis, it provides new tools and insights that could lead to future breakthroughs. This enhances our ability to make accurate predictions in number theory, potentially influencing cryptographic methods and data security by offering deeper insights into prime number behavior.

what’s next for primes?

These numbers also reveal connections between disparate areas of mathematics, such as number theory and complex analysis. Researchers use special primes to test mathematical conjectures and explore new theoretical territories. Historically, many prime types are named after mathematicians who made significant discoveries, documenting the evolution of mathematical thought. Some, like Mersenne primes, have practical applications in generating pseudorandom numbers and optimizing certain algorithms. The ongoing study of these primes continually expands mathematical knowledge and opens new avenues for research. Their unique characteristics and far-reaching implications maintain their relevance in both theoretical and applied mathematics.

Mathematics often advances through the exploration of seemingly abstract patterns. These theoretical concepts frequently interconnect in unexpected ways, revealing hidden relationships within the discipline. Prime numbers, despite their elementary definition, continue to harbor profound mysteries that challenge mathematicians worldwide.

The historical significance of certain prime types extends beyond their current applications, marking crucial developments in mathematical thinking. What appears to be a mere curiosity today may become fundamental to solving critical problems in the future.

While AI may benefit primality studies, no notable AI breakthroughs exist yet. Predictive models can estimate a number’s primality, narrowing search ranges for large primes. However, discovering very large primes, like Mersenne primes, relies on distributed computing projects using traditional algorithms.

These persistent puzzles underscore the depth and complexity of prime numbers, driving ongoing research and innovation in mathematics.

types of prime numbers

- mersenne primes: Primes where Mp = 2^p – 1, where p is prime and Mp is also prime. Examples: The first few Mersenne primes are 3, 7, 31, 127, 8191. I tell a lot of friends happy 31st birthday, it’s (likely) the last time you’ll be a Mersenne prime.

- twin primes: Pairs of prime numbers that differ by 2 (e.g., 3 and 5, 11 and 13).

- sophie germain primes: Primes p where 2p + 1 is also prime. 11 is a Sophie Germain prime because 2(11) + 1 = 23, which is also prime.

- fermat primes: Primes of the form 2^(2^n) + 1. 17 is a Fermat prime because 17 = 2^(2^2) + 1 = 2^4 + 1 = 16 + 1 = 17

- wieferich primes: Primes p where p^2 divides 2^(p-1) – 1. Example: 1093 and 3511 are the only two known (all primes up to 6.7 × 10^15 have been checked).

- wagstaff primes: Primes of the form (2^p + 1)/3, where p is an odd prime.

- circular primes: Primes that remain prime under cyclic permutation of digits. Example: 197 (971 and 719 are also prime)

- chen primes: Primes p where p + 2 is either prime or the product of two primes. 3 is a Chen prime because 3 + 2 = 5, which is prime

- gaussian primes: Complex numbers whose norm is a prime number. 2 + 3i is a Gaussian prime (its norm is 13, which is prime)

- primorial primes: Primes of the form p# ± 1, where p# is the product of all primes ≤ p. 5# – 1 = (2 × 3 × 5) – 1 = 30 – 1 = 29, which is prime