In high school, I had a book on my shelf titled Postmodern Theory by Steven Best. It was supposed to help me with Lincoln Douglas debate—something to give me an edge over my competitors in understanding the abstract and convoluted. The truth is, I barely understood it and didn’t read past the first chapter. But having it on my shelf felt important. It was a badge of intellectual curiosity, a symbol of grappling with an idea tossed around my friend group and within larger cultural conversations I wanted to be a part of. Eventually, I gave the unearned badge book away to a friend who studied philosophy in college. Years later, postmodernism still feels elusive—yet it’s more relevant than ever as we confront a world where AI and technology blur the lines between art, reality, and power.”

what is postmodern art?

Postmodernism is not just about self-aware art aka art that knows it’s art—it’s a philosophy that subverts traditional narratives, blending high and low culture, and questioning the very structures we rely on to make sense of the world. It’s a philosophy of self-awareness, subversion, and endless questioning. Where modernism sought to explain or transcend, postmodernism revels in the collapse of these larger narratives, the blending of high and low culture, the idea that (almost) anything can be art if it questions what art is supposed to be. It’s playful, often purposefully opaque, and sometimes alienating. But that’s part of its charm—or its frustration.

It can be both relatable and alienating at the same time. It holds up a mirror to the world, but that mirror might be cracked or distorted, forcing us to see ourselves in ways we’d rather not. It challenges the traditional ways we interpret everyday objects, spaces, and even people. In that way, postmodernism becomes less about the art itself and more about the experience of engaging with it, constantly questioning our assumptions about reality.

obfuscation or revelation?

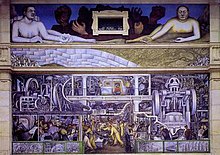

Noam Chomsky, for instance, has famously called it purposefully obfuscating, arguing that it deals in abstraction and avoids the hard truths of reality. For Chomsky, postmodernism’s conceptual nature distracts from the material, from the problems that can and should be addressed through direct, clear action. We should look to work’s like Diego Rivera’s Detroit Industry Murals or Ai Weiwei’s politically charged installations as great works of art as they both engages with and critiques real-world structures without obscuring meaning.

But I’m not convinced that postmodern art is as disconnected from reality as Chomsky suggests. Yes, it can be self-referential to a fault—opaque, obscure, and alienating. Yet it also possesses the power to confront us with difficult questions about our material, real world.

Take Andy Warhol’s Campbell’s Soup Cans: it’s both absurd and profound, elevating the mundane to the level of high art while making us question why we ever separated the two in the first place. Postmodernism doesn’t avoid reality; it forces us to confront the constructed nature of our perceptions. It’s not that it ignores the “hard truths,” but rather it asks us to consider whether the truths we hold so dear are as solid as we think.

can postmodernism be accidental?

If there’s one thing I’ve come to believe about postmodernism, it’s that it must be intentional. You can’t stumble into postmodernism the way you might accidentally fall into a modernist aesthetic or stumble across a realist narrative. Postmodernism requires a deliberate choice to engage with the fractured, the self-aware, the subversive. The artist must be in on the joke, or the commentary, or whatever critique is being leveled.

This is where postmodernism becomes both its most fascinating and its most frustrating. Because it’s a conscious movement, there’s always the danger of trying too hard, of becoming self-referential to the point of exhaustion. But when it works—when the artist nails that delicate balance between knowingness and creativity—it can be revolutionary.

Michael Heizer’s Levitated Mass, a giant boulder suspended above a walkway at LACMA.

The absurdity of the piece is that the boulder itself is the easiest part; moving it was a logistical nightmare, an engineering feat that cost millions. It’s both a massive waste of effort and a profound statement on effort itself. Heizer’s work embodies the core of postmodernism: an art piece that knows it’s a spectacle, yet forces us to consider the absurd lengths we go to in order to make art meaningful.

The deliberateness of postmodernism ensures that it stays a challenge to the viewer. You can’t accidentally make postmodern art because, by definition, it’s about questioning the very nature of art. This leads to a constant negotiation of boundaries (and as a self-identified business man, boy do I love negotiation) —not just within the art world, but in the way we engage with culture and, more broadly, the human experience. In an age where technology is blurring the lines between creator and creation, that negotiation has never been more important.

reality, or a blurring of the real?

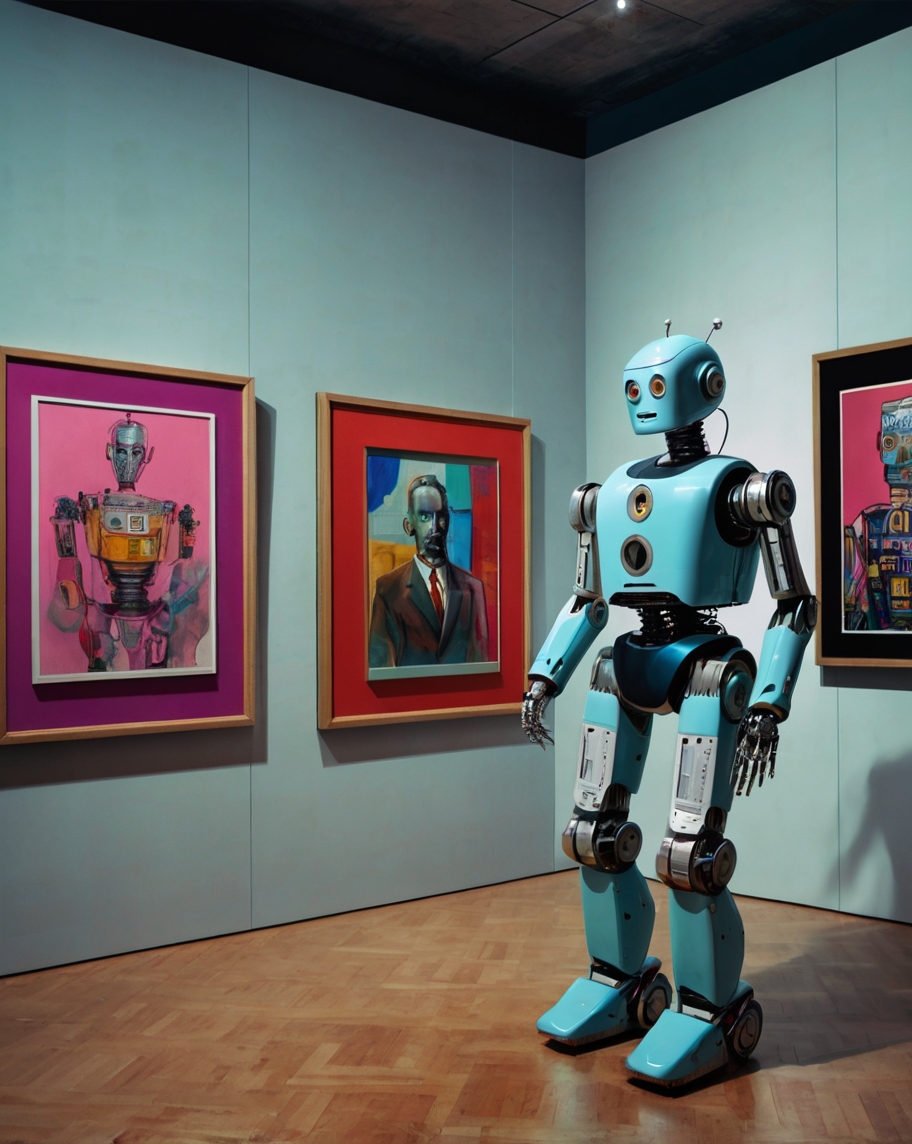

Postmodernism, at its core, is concerned with questioning the nature of reality. In the 20th century, this often meant playing with the boundaries between the authentic and the artificial. Today, with the rise of AI #theriseofAI #buzzzzzword, those boundaries are not just blurred—they’re dissolving entirely. Deepfakes and large language models challenge our ability to distinguish between what is “real” and what is generated. We’ve entered an era where machines create art, generate narratives, and produce human-like content that, at first glance, feels authentic. But is it? Did this AI-aided paragraph feel authentic enough?

Consider the phenomenon of AI-generated art. While an algorithm can mimic the brushstrokes of a master, does it possess the creative intent behind those strokes? No. Postmodernism, with its love of irony and self-reference, might argue that the AI’s lack of human intent is precisely the point. It’s not about the “truth” of the artwork, but about how we perceive it. AI forces us to re-litigate our definitions of originality, authorship, and meaning. When a machine can generate a sonnet or a painting indistinguishable from human work, we’re left with an essential postmodern question: does it even matter who—or what—created it, as long as we experience it as art?

ai and the multiplicity of truth

Postmodernism has long critiqued grand narratives—those sweeping, all-encompassing stories we tell ourselves to make sense of the world. From religion to nationalism, postmodern thinkers have sought to dismantle these absolute truths, arguing that reality is more fragmented and subjective than we might like to admit.

AI helps reveal inconsistencies in established narratives. AI models, like those used to analyze historical texts or media, can highlight the biases and gaps in our stories. These systems, built on data, don’t just challenge singular interpretations of events; they generate multiple, often contradictory, narratives. For example, an AI might generate various historical interpretations based on different datasets, revealing how fluid our understanding of truth can be.

But it’s not just about exposing inconsistencies. AI also has the potential to create entirely new narratives. Imagine a future where AI writes historical textbooks, offering not one account of history, but many, all equally plausible. In some ways, this is the ultimate postmodern project: a world where there is more relative truth or layers of meaning waiting to be deconstructed.

who owns creativity?

One of the most intriguing questions postmodernism poses is: who owns the idea of creativity? Andy Warhol famously outsourced much of his artistic production, questioning the notion of original authorship. Was it Warhol’s hand that made the art, or his idea, or perhaps the factory workers who executed his vision? Art collectors definitely think it’s Warhol. In today’s world, AI-generated content forces us to revisit this question on an even larger scale. When an AI generates a poem, a painting, or even a news article, who is the creator?

Postmodernism challenges the idea that any art is truly original. All art, it argues, is a remix—a reinterpretation of what came before. AI takes this to its logical extreme, producing works that are statistical recombinations of existing patterns. But the lack of human intent complicates things further. If a machine can replicate the creative process without consciousness, does it still count as art? Or are we simply participating in a collective hallucination, convinced of the work’s value because it looks and feels like something created by a human?

Warhol’s experimentations with authorship now seem like a precursor to the dilemmas we face with AI. And while we may still credit the artist over the machine, the lines between human and machine creativity are becoming increasingly hard to discern.

living in ai-generated hyperreality

Postmodernism revels in fragmentation, in breaking down the seamless experiences modernism sought to construct. Jean Baudrillard’s idea of hyperreality—the point at which the simulation of reality becomes more real than reality itself—seems eerily prescient in our AI-driven world. Today, we live in personalized information bubbles curated by AI algorithms, where our digital experiences are tailored to fit our preferences, often to the exclusion of competing viewpoints.

Social media algorithms fragment our perception of reality, serving up content that aligns with our existing beliefs and reinforcing our biases. In a postmodern sense, these algorithms create a hyperreal environment where what we experience online feels more authentic than the messy, contradictory world outside; the clash of opposing ideas in our minds can be confusing and challenging to resolve. This hyperreality, created by machines, deepens the fragmentation that postmodern thinkers have long critiqued.

The personalized nature of these algorithms only amplifies the postmodern condition—our lives, once structured by grand narratives, are now splintered into individual streams of curated content. The world itself feels less cohesive, more fragmented, more tailored to our immediate desires. And this is perhaps the most profound postmodern irony: the more these machines cater to us, the less we understand ourselves and outsource the creation of our thoughts and potentially our identities.

can machines truly understand?

Postmodernism has always been fascinated by language, by the ways in which it shapes our understanding of reality. Jacques Derrida’s concept of deconstruction—the idea that language is inherently unstable and that meaning is always deferred—speaks directly to the challenges posed by AI language models. These models, trained on vast amounts of text, generate language that seems to have meaning.

AI demonstrates that language, at least in its construction, can be boiled down to statistical patterns. A machine doesn’t (yet) understand the words it’s generating—it simply predicts what word should come next based on probability. For postmodernists, this lack of “true” understanding underscores the fragility of meaning itself. If machines can create language without consciousness, what does that say about the relationship between language and thought? Have we, as humans, overestimated the significance of our own linguistic capabilities?

This is where postmodernism and AI intersect in a particularly fascinating way. Both expose the constructed nature of meaning—one through philosophical inquiry, the other through mathematical models.

who controls the machines?

Postmodernism has long critiqued power structures—those systems that shape knowledge, culture, and society. Michel Foucault argued that power isn’t just held by governments or institutions; it’s embedded in the very ways we come to understand the world. Today, AI systems, controlled by a handful of tech companies, raise new questions about power and knowledge creation.

AI is built on data, and data is power. The companies that control the most data wield significant influence over what we see, what we know, and even how we think. In this sense, AI becomes not just a tool for creating art or content, but a powerful force shaping our collective reality. The algorithms that guide our decisions—what we read, what we watch, even what we believe—are controlled by entities we cannot see or fully understand.

This is the ultimate postmodern dilemma: a world where the structures of power are more diffuse, yet more pervasive, than ever. In an age where machines generate the content we consume, who holds the real power? And how can we, as individuals, reclaim agency in a world increasingly defined by algorithms?

As Donna Haraway, author of A Cyborg Manifesto (1985), reminds us, the postmodern focus on fragmentation is no longer enough—we must actively engage with the systems shaping our world. In the AI age, that means rethinking power, identity, and agency as fluid, interconnected forces

what’s postmodernism’s future?

As we navigate the digital age, postmodernism continues to evolve, shaped by the very technologies that blur the boundaries between reality and simulation, originality and replication, human and machine. AI, in its ability to create and curate, forces us to confront the questions that postmodernism has been asking for decades: What is real? What is original? Who controls the narrative?

Postmodernism may have started as an intellectual and artistic movement, but in today’s world, it feels more like a survival mechanism—a way of making sense of the fragmented, hyperreal, and algorithmically driven realities we inhabit. In this new age, postmodernism isn’t just playing a bigger part in art and writing—it’s redefining what it means to be human.