In America, an air traffic controller must retire by age 56. A federal firefighter? Out at 57. FBI agent? Same. But the person with unilateral control over the nuclear launch codes? The person who nominates Supreme Court justices and sets the tone of national and global policy? That person can be 78, 84, 91, and keep going—as long as they can still win elections or cling to incumbency. No test. No limit. No mandated exit.

This is the paradox of American age policy: the higher the stakes, the looser the rules.

We have designed a system where early retirement is aggressively enforced for technical roles that demand split-second reflexes and precision. Air traffic controllers, who quite literally keep planes from colliding in the sky, are forced out before most people hit their late-50s stride. The justification: safety. Cognitive decline. Fatigue risk.

But when it comes to senators drafting climate policy, or judges ruling on constitutional rights, or a president ordering drone strikes or pardons, we trust that age is just a number. Our most powerful institutions are allergic to age limits. And the implications are getting harder to ignore.

curious cases of mandatory retirement

Mandatory retirement ages exist in dozens of roles across the U.S. federal workforce. Law enforcement officers under Title 5 retirement rules must leave by 57. The logic? It’s a young person’s job. FBI agents and Secret Service officers are required to maintain a high level of physical fitness and resilience under pressure. The same logic applies to federal firefighters and air traffic controllers.

Commercial airline pilots? Grounded at 65. That number only recently moved from 60 in 2007 after intense lobbying. Pilots have even proposed pushing it to 67, citing longer life spans and workforce shortages. But in most high-risk occupations, early retirement isn’t a suggestion—it’s law.

And these laws are enforced strictly. There are no term extensions, no votes to override the rule. You don’t get to test out. Once you hit the number, you’re done.

Unless, of course, you’re at the top.

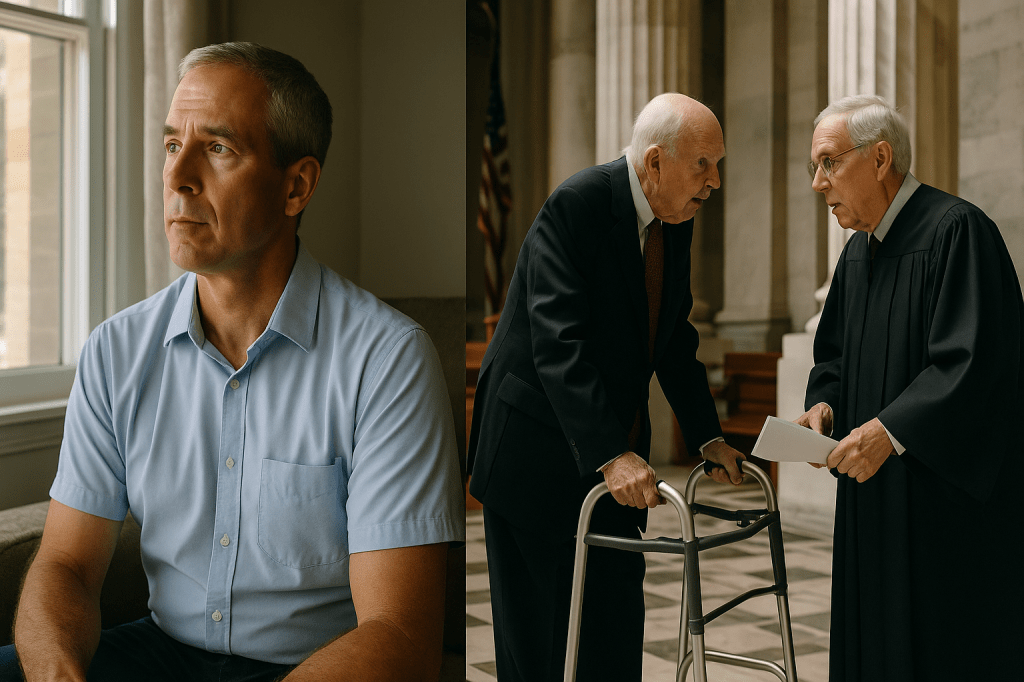

Supreme Court justices in the U.S. serve for life. There is no age cap, no routine mental or physical assessment, and no formal process for removal unless they retire or are impeached—a nearly impossible political feat. Many state courts have age limits (New York, for example, mandates retirement at 70), but the federal judiciary remains exempt.

Members of Congress can serve indefinitely, and often do. Strom Thurmond retired at 100. Dianne Feinstein remained in office while visibly struggling with memory and cognition. The idea of mandatory retirement is treated as an affront to voter choice, even when the job involves lifetime appointments or the power to legislate for 330 million people.

Presidents must be at least 35 to run but face no upper age limit. Ronald Reagan left office at 77. Joe Biden is currently 82. Donald Trump is 78.

We run pilots through simulators and fitness checks. Air traffic controllers receive rigorous cognitive testing. But presidents? Nothing beyond public debates, media scrutiny, and their own campaign trail stamina.

who limits their leaders?

Many other countries place age caps or retirement rules on high office.

- China: Politburo members are typically required to retire at 68 under the “seven up, eight down” rule, though Xi Jinping has broken precedent.

- Japan: Supreme Court justices must retire at 70.

- France: Judges retire at 70; public servants often face mandatory retirement at 67.

- India: Supreme Court justices retire at 65.

- Germany: Constitutional Court judges must retire at 68.

- Brazil: Supreme Federal Court justices retire at 75.

These policies exist not because those countries value age less, but because they value institutional clarity and performance consistency. They also avoid the awkwardness of open-ended tenure. You can love someone’s legacy and still recognize when it’s time to go.

In the U.S., our deference to seniority often becomes deference to inertia. Power stays where it accumulates. That’s why the people most affected by mandatory retirement laws are not the ones writing them.

can we do better?

What if we applied the same standards to political leadership that we apply to pilots or agents? Not ageism, but fitness-based evaluation. Simple annual assessments: cognitive screening, response-time tests, stress evaluations. They wouldn’t disqualify the healthy—just catch the declines that can endanger judgment.

We could also consider term limits or phased retirements for the judiciary. Instead of life tenure, a 20-year term. Or mandatory reviews after age 75.

If a 56-year-old controller is too old to route a 747, a 90-year-old senator is certainly too old to regulate AI or decide reproductive rights.

downward accountability

America’s retirement laws reveal something deeper: we enforce accountability downward, not upward. The people with the least autonomy get the strictest rules. The people with the most power get the most leniency.

That’s not about safety. It’s about politics. It’s about the myth of wisdom through age, the fantasy that time in office equals insight, and the fear of telling powerful people it might be time to leave.

And yet, if we truly value performance, fairness, and safety—shouldn’t the stakes demand more of our leaders, not less?

Maybe the first test of power should be the willingness to let go of it.